What do Sherlock Holmes, a self-obsessed musical automaton and a robotic bin have in common? The TEDx University of Edinburgh conference, of course.For those of you who weren’t able to attend this weird and wonderful event, I will be covering the best and strangest talks this conference had to offer.

The theme this year was ‘The Great Unknown’ bringing together a unique group of speakers who shared how they were using innovation, technology and AI to change our world for the better.

The first speaker was really enthusiastic about proteins. Yep, you read that right, the Biomedical Ph.D. student Leonardo Castorina specialises in AI-driven protein design and immune system research. He gave a passionate talk about the different ways AI could improve healthcare delivery and take some of the burden off our burnt-out and stressed medical practitioners. Castorina shared some of his impressive work experiences with us, from his work in using AI to improve the resolution of MRI images to his current research into how AI can help us identify the most likely antibody for a virus. I don’t know about the rest of the audience, but his talk certainly left me feeling much better about facing any future pandemics with AI as an ally.

Next, we heard from a speaker who started her presentation with a call to arms against computers and technology and ended it by revealing she was Edinburgh University’s very own professor of informatics. Elizabeth Polgreen horrified the captivated audience with scary stories about computer errors that have killed people. The story I will forever have imprinted in my brain is that of Therac-25, a radiotherapy machine which due to a computer bug, delivered over 100 times the prescribed radiation to patients and killed six individuals.Having convincingly made the case that computers can be dangerous and unreliable, she then proceeded to argue that Sherlock Holmes’ impeccable logical reasoning skills might help us to make computers and AI programs more reliable. Dr Polgreen explained that just like Sherlock in his cases, we can use ‘proof theoretic’ reasoning and ‘model-theoretic’ reasoning to create automated verification systems that can test the reliability of AI. Emphasizing the importance of verification systems, she stressed that they should become something that we expect from software and AI programs.

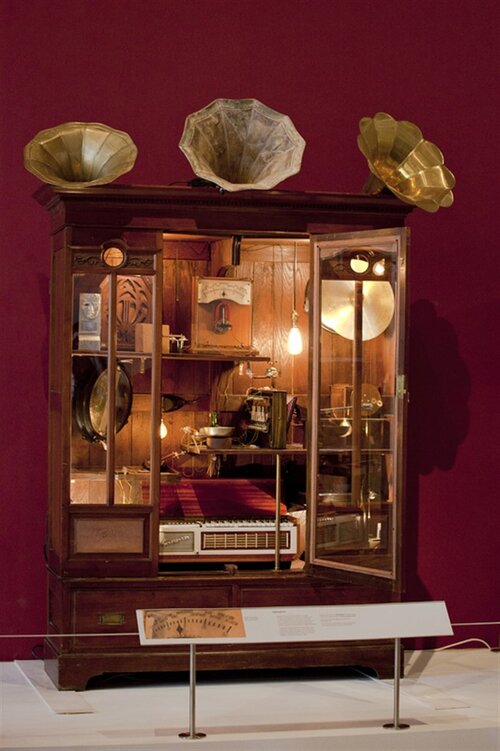

We then heard from a musical automaton named Cybraphon and, of course, its creator Simon Kirby. Cybraphon is described as “an emotional robotic band built from junk shop instruments, housed in an antique wardrobe, that googled itself every 15 seconds”. The artwork was commissioned in 2009 to be reflective of the growing obsession with social media platforms, it is one of Twitter’s first-ever “bots” and regularly tweets its mood (which is dictated by its popularity online) to its many followers.

Professor Kirby shared with us his surprise at how individuals would sit in front of Cybraphon and chat with it on Twitter, treating it like a human being and even giving suggestions to improve its mood. Though it’s difficult to confuse a giant wardrobe machine with a human, Professor Kirby raised concerns about newer chatbots and incredibly sophisticated forms of AI giving the impression of perfection. He suggested that perhaps chatbots like ChatGPT should be engendered with flaws or at the very least wear the flaws they do have on their sleeve.

Jonathan Feldstein introduced us to Janus, which I can safely say is the coolest rubbish bin I have ever seen. Janus automatically sorts waste: reducing human error and decreasing contamination by automatically removing liquids. Feldstein claims that by using Janus (consequently increasing recycling rates) 20 tons of CO2 can be saved.

Feldstein also shared with us some pretty realistic views about what humans are willing to do and for what. He argues that to fix climate change fear, charity and hope make for bad motivators. What we should be focusing on is models with low cost of action, high reward, and most importantly short delays in gratification. For this reason, Feldstein’s business model for Janus avoids a high fixed price and uses a service fee instead. This, he argues, allows businesses to save money from day one, to continue introducing new features to the product and to increase the product lifetime (polluting less). Feldstein believes that by short-circuiting the reward cycle, sustainable choices become smart financial choices.

Each speaker had a powerful message, be it their hopes for what technology can achieve or their warnings for what it might entail. The future remains a ‘great unknown’ but talks like these give us a sneak peek at what we might expect.

Written by Celene Sandiford, smartR AI